Photo by William Warby on Pexels.com

I recently finished reading An Immense World by Ed Yong. The book covers an overview of how animals use their senses in substantially different ways from humans. Some of the information is well known. Dogs have a sense of smell that is somewhere between 10,000 to 100,000 time better than humans. Bats use an echolocation “sense” to navigate at high speeds in the dark to locate miniscule flying game. Birds of prey (eagles, falcons, etc.) have superior eyesight that allows them to see forward and sideways to best home in on a meal. The book however goes deeper and helps the reader understand that most every “superiority” is balanced.

The dog has a remarkable sense of smell, but their eyes have only two color photoreceptors, so their world looks different than what humans see. Humans have three photoreceptors, a handful are tetrachromats with the benefit of four (I wrote about this phenomenon in a previous post: “Tetrachromatic Vision” https://lightingbyjeffrey.com/2022/05/09/tetrachromatic-vision/ ) but the mantis shrimp has TWELVE photoreceptors! Wow! You’d think their sight was miraculous, but alas, they have a tiny brain (brain size and functional capacity is a crucial piece of data in these analyses) so rather than witnessing colors beyond our imagination, they use the twelve photoreceptors as a type of binary coding system. If, for example photoreceptor one, three and eleven are triggered, they know prey is within reach. If photoreceptor two, eight and nine send feedback to the brain, it is time to move, an enemy is near. All benefits are balanced by Mother Nature.

Humans are sighted creatures and we regard the world based on sighted preferences. (I wrote about this in yet another post: “Eyes, Light and Sometimes, Brain” https://wordpress.com/post/lightingbyjeffrey.com/684 ) When we do that, we ignore the needs and demands of the other animals who occupy the planet. Even other animals who enjoy sight as their primary sense, do not use it in the same way as humans. Owls need dark nights to survive. The lack of light and their ability to see in it, sustains them. Bees have three photoreceptors, but because they can see UV light, the three receptors read different information and feed that back to the brain, so their color palette is radically different from ours.

Humans have risen to the top of the community of earth’s animals and our single-minded concern with human need is unfortunately harming the greater animal community. This summation ended the book. The human need to illuminate “everything” is doing irreparable harm to other animals. It is only getting worse, despite an avalanche of data on animals and their worlds. We read books like An Immense World and still increase street lighting, parking lot lights and high-rise building illumination. After becoming enamored with the content of the book, his plea to the reader is for some kind of action.

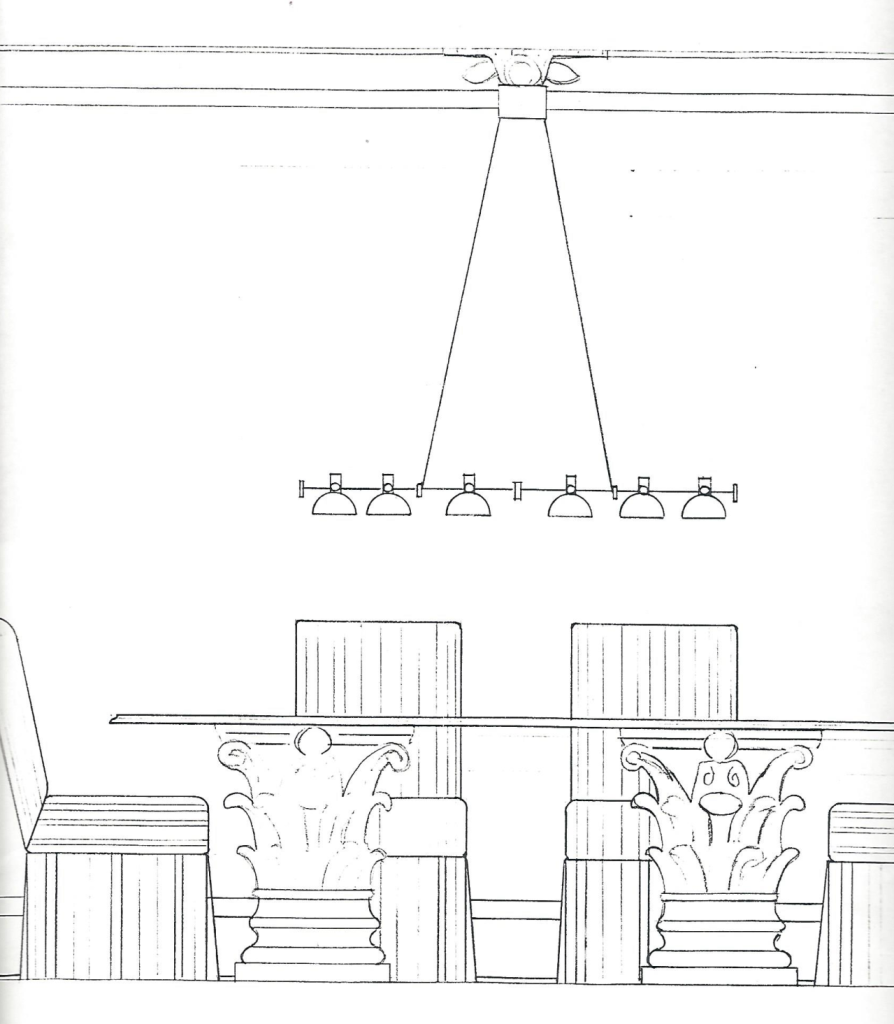

As a lighting community, we can do better. I’ve just looked at a wide variety of new luminaires released at the January Dallas Market and still we offer light aimed up into the sky where it does no good and only delivers harm to plants and animal. We use lumen levels way beyond what is necessary and that color of light is often blue, not only bad for humans, but many in the animal community are likewise impacted.

Can we help? We are in a unique situation to do just that. We can’t help much directly with pollution, micro-plastics in the oceans or noise levels that also impact, confuse and confound animals, but we can control light. That’s what we do as lighting professionals. Could we start to include concern outside of our genetic spectrum in addition to the color spectrum?